Beyond the Efficient Market Hypothesis - Capitalizing on Modern Market Anomalies

3 December, 2024

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), introduced by Eugene Fama in 1970, has long been a cornerstone of financial theory, asserting that asset prices fully reflect all available information. This principle suggests that markets are inherently efficient, leaving no room for consistent outperformance. For decades, it served as a theoretical foundation for the rise of passive investment strategies, such as index funds, which aim to mirror market performance rather than exceed it.

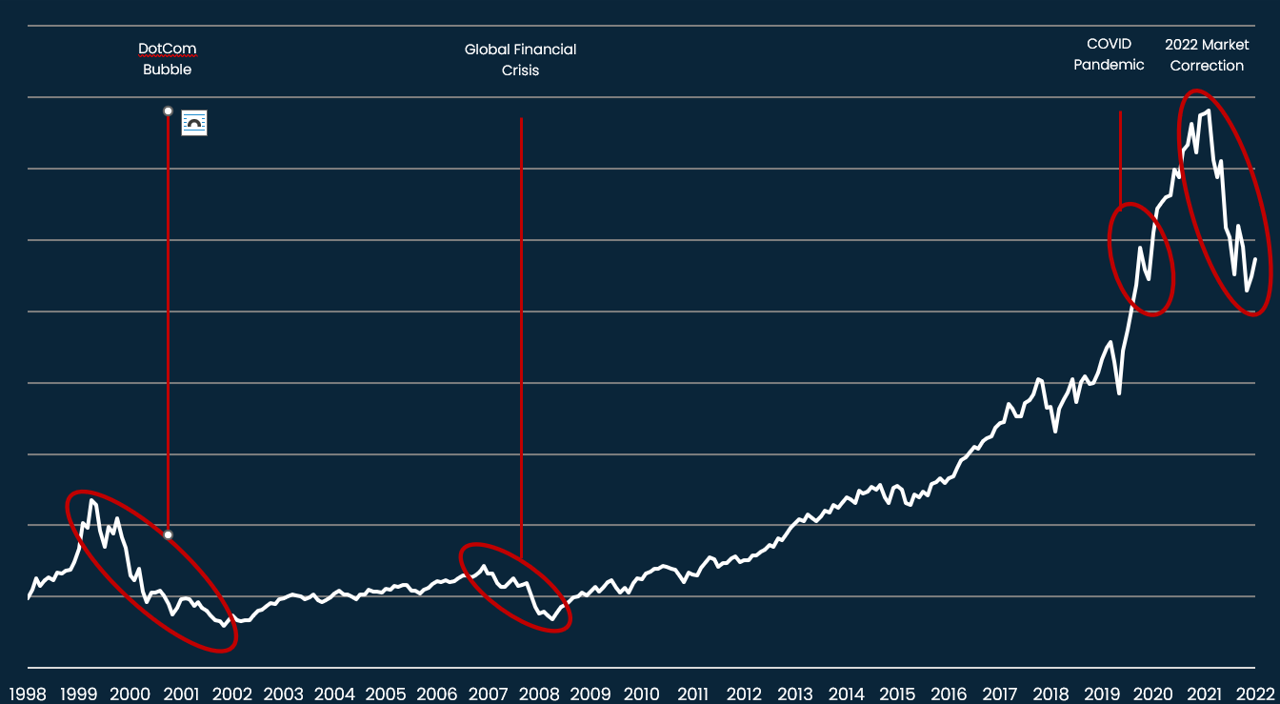

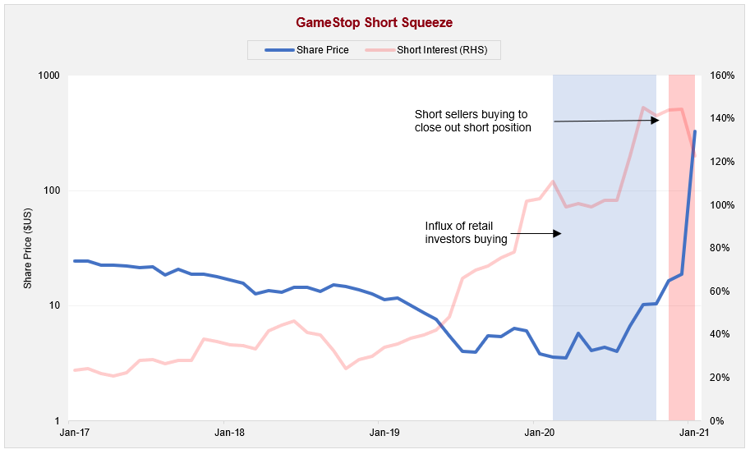

Fast forward to 2024, and the financial landscape continues to test the limits of the EMH. Market anomalies, once considered exceptions, have grown increasingly prevalent in the face of new technologies, social dynamics, and trading strategies. High-profile events like the 2013 "flash crash," where the U.S. stock market plunged nearly 9% in minutes due to algorithmic trading and investor panic, exposed the fragility of the EMH's assumptions. More recently, disruptions caused by the 2021 GameStop short squeeze and volatility in cryptocurrency markets have further underscored the influence of behavioral biases, social media, and herd mentality on market efficiency. These developments suggest that markets are not as rational or efficient as previously believed.

The Adaptive Markets Hypothesis (AMH) offers a fresh framework for understanding these dynamics. It acknowledges that while markets are often efficient, they can falter under stress or shifting conditions. Events like the flash crash and persistent mispricing in emerging asset classes highlight how inefficiencies arise, presenting opportunities for investors equipped with the right tools and insights. For instance, leveraging advanced data analytics and behavioral finance principles allows investors to detect these inefficiencies and capitalize on them strategically.

This article examines how new approaches in quantitative finance and behavioral insights are reshaping investment strategies in light of market inefficiencies. Far from signaling the end of efficient market principles, these advancements highlight the importance of adaptability and innovation for those looking to thrive in an increasingly complex financial ecosystem.

The Traditional Investment Paradigm

The Efficient Market Hypothesis has long been the foundational framework for understanding whether “picking winners” from a pool of investment opportunities can lead to sustained outperformance over time. Specifically, in the context of equities, EMH suggests that active managers, who attempt to select stocks and construct portfolios, are unlikely to consistently outperform the broader market over the long term. This efficiency is rooted in the idea that market prices reflect all available information, with the assumption that the price of an asset represents an unbiased estimate of its true value.

Core Tenets of the Traditional Investment Paradigm

The traditional investment paradigm, grounded in the EMH, rests on several key assumptions:

- Risk-Reward Tradeoff. There exists a positive relationship between risk and reward across all financial investments. The expectation is that assets with higher risk levels should yield higher returns to compensate for that risk.

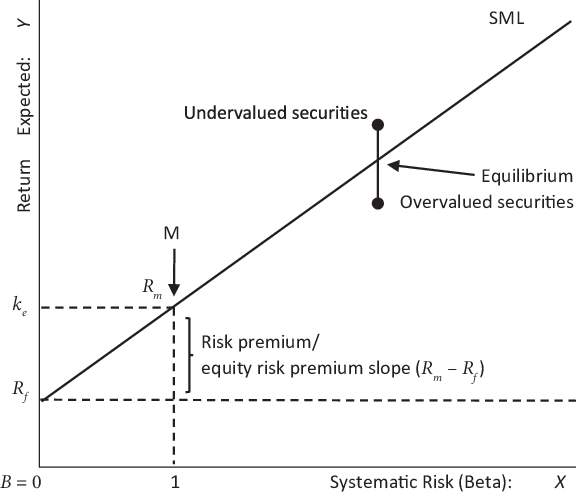

- Linear Relationship of Risk and Return. The tradeoff between risk and return is presumed to be linear. Risk is typically measured by beta (β), which represents a stock’s sensitivity to market movements, and alpha (α), which reflects the excess return of a portfolio relative to a market benchmark (e.g., the S&P 500).

- Passive Investment Approach. According to traditional theory, investment returns are best achieved through passive, long-only, highly diversified equity portfolios. These portfolios are market-cap weighted, containing only equity betas, with no expectation of generating alpha (i.e., returns beyond what is attributable to market movements).

- Strategic Asset Allocation. The central task for investors is to determine the optimal allocation of their wealth across different asset classes to balance their risk tolerance and long-term investment objectives.

- Long-Term Investment in Equities. Traditional theory holds that all investors should adopt a long-term approach to equity investment, trusting that stocks will yield the best returns over extended periods.

While these assumptions served as reasonable approximations for financial markets from the 1930s through the mid-2000s—an era of relatively stable financial environments and regulations—the limitations of these assumptions have become increasingly evident in recent years. The increasing complexity of financial markets has led to growing skepticism about the continued relevance of the traditional investment paradigm.

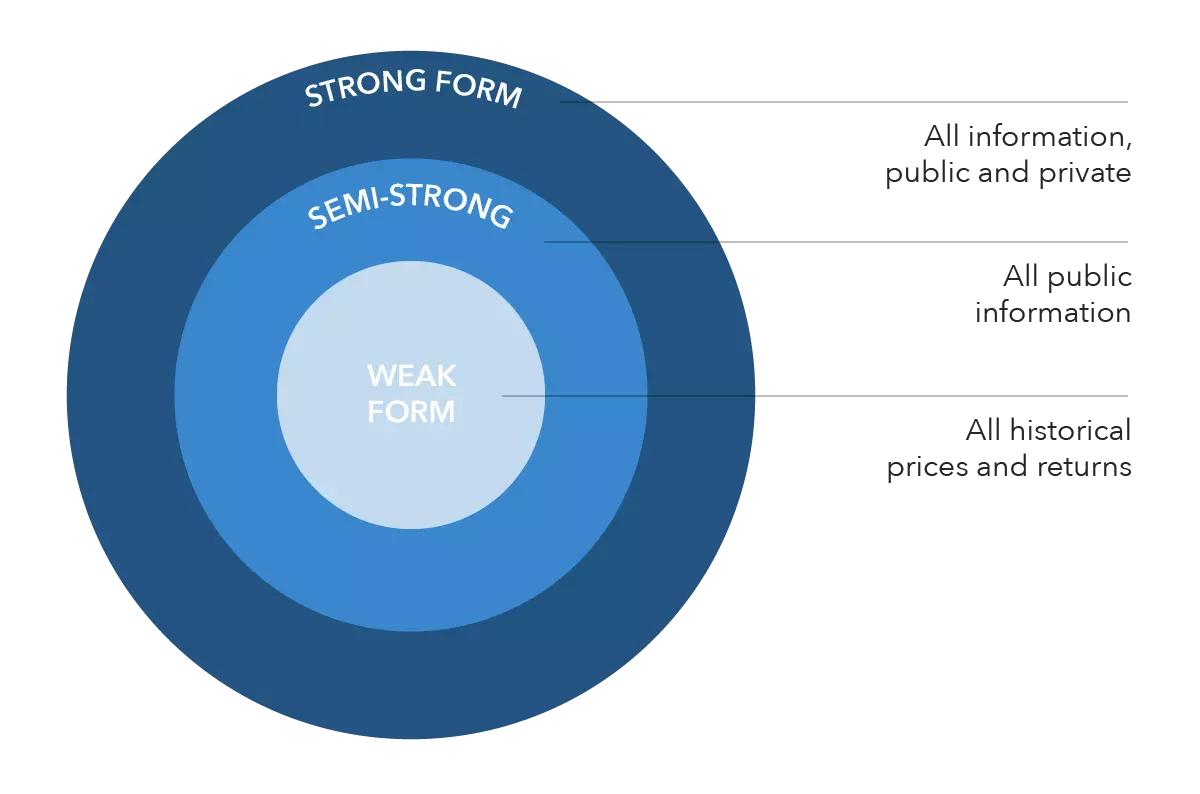

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) Explained

The core premise of EMH is that markets are informationally efficient, meaning that all publicly available information is immediately incorporated into asset prices. This belief is based on several key assumptions:

- Rational Investors: Investors are presumed to be rational, with their decisions based on the fundamental value of assets, which is calculated as the present value of expected future cash flows, discounted at a rate reflecting the associated risk.

- Information Reflection: In an efficient market, investors rapidly integrate new information into asset prices. As news about changes in expected future cash flows or shifts in risk emerges, asset prices adjust accordingly.

- Arbitrage and Price Correction: If irrational investors push asset prices away from their fundamental values, rational arbitrageurs will quickly exploit these mispricings by buying undervalued assets and selling overvalued ones, ultimately restoring equilibrium.

Proponents of EMH argue that, in efficient markets, no one can consistently outperform the market because all publicly available information is already embedded in asset prices. Even in cases where irrational investors act in a correlated manner, rational arbitrageurs will correct these inefficiencies, ensuring that prices converge to their true, fundamental values.

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and Portfolio Theory

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and Markowitz Portfolio Theory are both key components of the traditional investment framework, underpinned by the assumption of efficient markets.

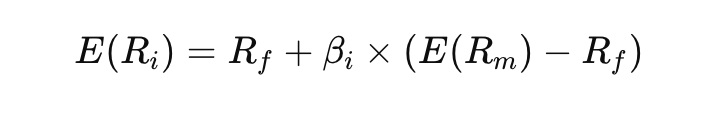

CAPM: The Capital Asset Pricing Model

The Capital Asset Pricing Model posits that the expected return of a security is linearly related to its systematic risk, as measured by beta (β). The relationship between risk and expected return is expressed by the formula:

Where:

- E(R_i) = Expected return of asset i

- R_f = Risk-free rate

- β_i = Beta of asset i

- E(R_m) = Expected return of the market

According to CAPM, investors should not expect returns beyond the risk-adjusted market rate. Any excess returns, known as alpha, are attributed to factors unrelated to market movements.

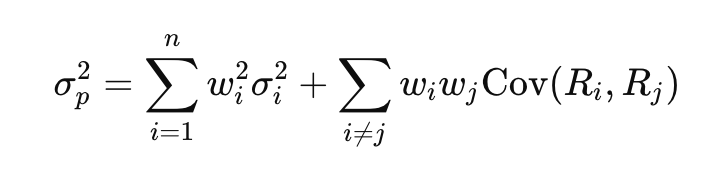

Markowitz Portfolio Theory

Markowitz’s theory emphasizes the importance of diversification in portfolio construction. By diversifying, an investor can minimize risk for a given level of expected return. The portfolio's risk is measured by the covariance between the returns of its individual assets. The efficient frontier represents portfolios that offer the highest expected return for a given level of risk.

The total risk of the portfolio is calculated as:

Where:

- σ_p^2 = Variance of the portfolio’s returns

- w_i = Weight of asset i in the portfolio

- σ_i^2 = Variance of asset i’s returns

- Cov(R_i, R_j) = Covariance between the returns of assets i and j

Markowitz’s model suggests that in an efficient market, investors should hold a well-diversified portfolio that mirrors the market portfolio. This approach minimizes risk while maximizing return, assuming that markets are fully efficient.

However, the increasing recognition of market inefficiencies and the limitations of both CAPM and Markowitz’s portfolio theory has led to ongoing debates about their applicability in contemporary financial markets.

Limitations of the Traditional Paradigm

While the traditional investment paradigm has long served as a cornerstone of financial theory, it faces growing scrutiny in the face of real-world complexities and evolving market dynamics. Several significant criticisms challenge its assumptions and practical relevance:

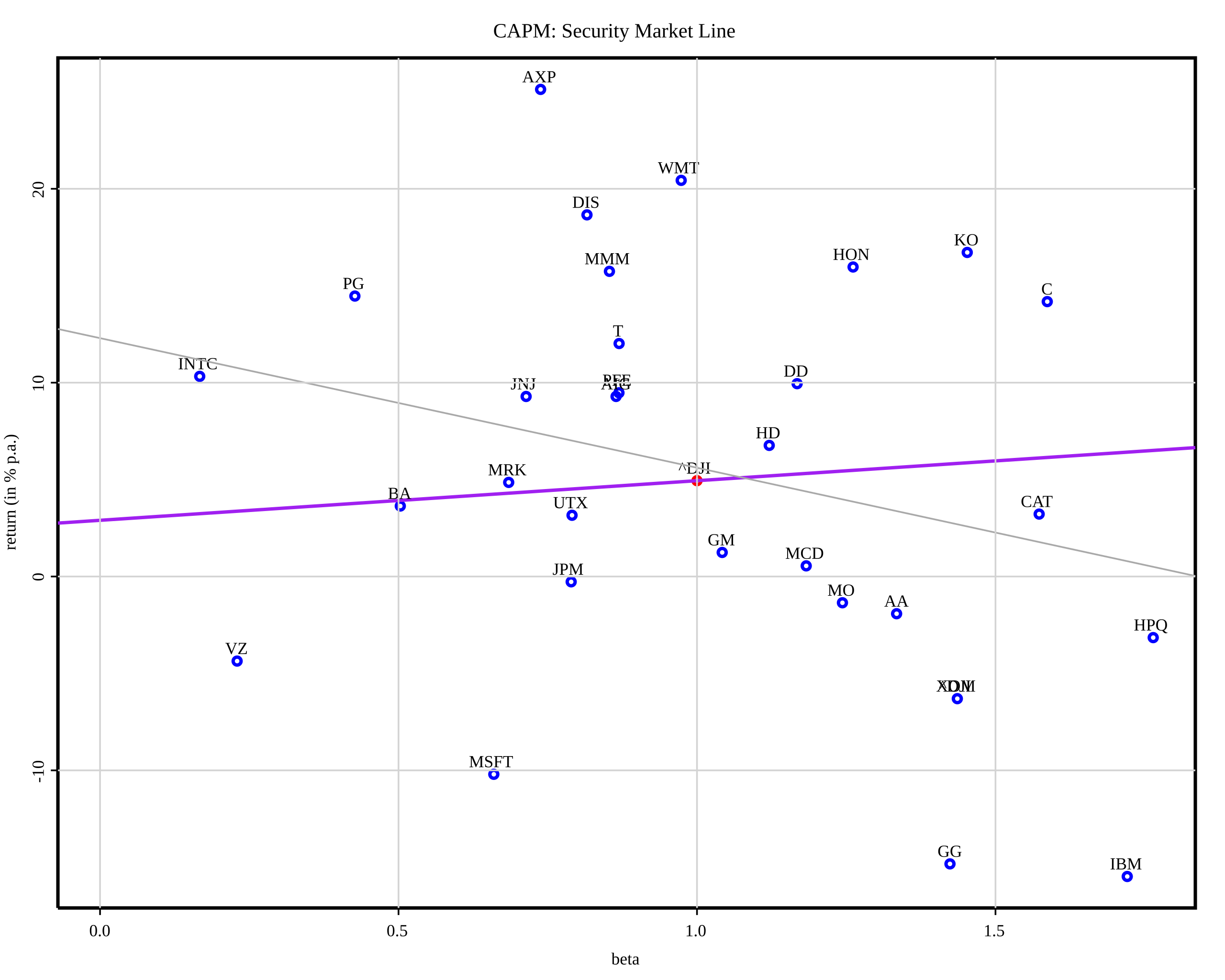

Empirical Limitations of CAPM

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), which posits a single market risk factor to explain asset returns, has increasingly come under empirical fire. Studies reveal that CAPM often fails to account for observed asset price movements, particularly over extended time horizons or in diverse global markets. In response, alternative models like the Fama-French three-factor model have emerged, adding size and value factors to market risk. While these models address some of CAPM's shortcomings, they remain reliant on historical regression analysis—a method criticized for its backward-looking nature and potential to mislead in dynamic, forward-focused markets.

Behavioral Critiques of Rationality

A cornerstone assumption of the traditional paradigm is investor rationality and market efficiency. However, behavioral finance has exposed the frequent divergence of real-world investor behavior from these assumptions. Psychological biases, such as overconfidence, herding, and loss aversion, alongside shifts in market sentiment, can lead to phenomena like bubbles and systematic mispricing. Traditional models often fail to account for these behavioral drivers, leaving gaps in their explanatory power.

In today’s volatile, technology-driven, and information-saturated financial landscape, the assumptions underlying traditional frameworks such as the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), CAPM, and Markowitz portfolio theory are increasingly out of sync with market realities. Some studies argue that traditional market analysis tools underestimate the prevalence of these opportunities, leaving gaps for skilled investors to exploit. This trend raises questions about whether market participants effectively process the vast array of available data—or if these inefficiencies represent untapped opportunities for those capable of navigating the modern financial landscape. While these theories remain foundational in financial economics, their limitations underscore the need for more adaptive and nuanced approaches to understanding and navigating contemporary markets.

The Behavioral Approach

Behavioral finance emerged as a response to the limitations of traditional financial theories in explaining certain market phenomena. Unlike the classical paradigm, which assumes that investors are rational and make decisions based on objective information, behavioral finance posits that investors can be irrational due to psychological biases and heuristics. These biases influence their perceptions of information, leading to errors in judgment and decision-making. Such irrational behavior can cause asset mispricing, where the market deviates from the expected values predicted by traditional models like the efficient market hypothesis (EMH).

Psychological sources of irrationality manifest in several ways. First, individuals are often overconfident in their judgments, as demonstrated by studies like Odean (1998) and Barber & Odean (2001). This overconfidence leads investors to trade excessively and take on more undiversified risk, often resulting in significant losses due to high transaction costs. Overconfidence and optimism also contribute to market overreactions, where asset prices swing too far in response to new information. Overconfidence occurs when individuals overestimate their knowledge or abilities. In finance, overconfidence can lead investors to underestimate the risks associated with their decisions or to overestimate their ability to outperform the market. This bias is often linked to excessive trading, as overconfident investors believe they have an edge in predicting market movements.

Additionally, social influence plays a significant role in irrational behavior. Investors often imitate each other, driven by the learning processes within social networks, direct interpersonal communication, or the influence of media. This herding behavior can amplify market mispricing, especially when investors disregard crucial information and chase trends based on popular opinion rather than fundamentals. Investors might overvalue news that is widely covered in the media, leading them to make decisions based on sensationalized or incomplete information. For example, an investor might be influenced by a news story about a company's short-term success, ignoring broader financial indicators that suggest the company may face long-term challenges.

These biases illustrate how psychological factors can distort investor behavior, making markets more prone to inefficiencies and asset mispricing. Traditional financial models, which assume rationality and market efficiency, often fail to account for these biases, highlighting the need for an alternative approach like behavioral finance.

Limits to Arbitrage and Misconceptions of Market Inefficiencies

Behavioral finance acknowledges that arbitrage plays a critical role in correcting market mispricings. However, it also highlights the practical limitations that make certain pricing deviations resistant to correction. Arbitrage strategies, while theoretically sound, often involve significant risks and costs. Transaction fees, bid-ask spreads, and the high costs of short selling can erode potential profits. Additionally, identifying mispricing requires substantial time and research, and even when opportunities are found, liquidity constraints or institutional restrictions, such as bans on short selling, can render them impractical.

Coordination challenges among arbitrageurs further compound the difficulty. A single trader often lacks the capital or influence to correct a significant mispricing alone, relying instead on collective action from others in the market. However, this coordination is inherently uncertain. Delays in action can diminish or eliminate profits, as the market may gradually correct itself or become more volatile before an arbitrage opportunity is fully exploited.

Misconceptions and Rationales for Active Management

Critiques of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) often misconstrue its premise, suggesting that efficient markets lack pricing errors entirely. In reality, the EMH asserts that while mispricings occur, they are random and cancel each other out over time, making it difficult for any investor to systematically outperform the market.

Historical examples underscore the unpredictability of pricing errors. During the late 1990s dot-com bubble, Amazon's stock soared despite the company's lack of profitability at the time. Many traders labeled the stock as overvalued and attempted to short it, expecting prices to fall. Instead, Amazon's price continued to rise, inflicting massive losses on short-sellers and defying traditional valuation models. Ultimately, the company's growth trajectory vindicated its valuation, but the episode highlighted the risks inherent in betting against perceived mispricing.

A similar dynamic unfolded during the 2008 financial crisis, when certain mortgage-backed securities (MBS) were believed to be underpriced due to exaggerated fears in the market. Some investors seized the opportunity to buy these securities, expecting a rebound in value. While the long-term recovery validated some investments, many faced significant short-term losses as the crisis deepened, exposing the challenges of acting on perceived mispricings.

The Role of Social Media and the Internet

The frequency of such anomalies appears to be rising, with many likely underreported or overlooked due to limitations in traditional analytical approaches. The rise of social media and the democratization of trading through online platforms has significantly altered the dynamics of market efficiency. Traditionally, an efficient market relies on a diverse group of market participants, each expressing independent opinions about asset values, thereby helping to create a fair price for all assets. However, social media has introduced a new dimension where the independence of individual investors can be compromised, and market efficiency is challenged. Platforms like Reddit, Twitter, and StockTwits have become influential in shaping investor behavior, often distorting the price discovery process.

An example of this occurred during the GameStop short squeeze in early 2021, which showcased how social media can disrupt traditional market mechanics. A group of retail investors on the Reddit forum r/WallStreetBets began to coordinate buying GameStop shares, driving the stock price up by more than 1,700% in a matter of weeks. This unprecedented price surge was largely fueled by collective action on social media, where misinformation, exaggerated claims, and emotional rallying cries overshadowed the underlying fundamentals of the company. Investors, many of whom had little to no experience in stock trading, were swept up in the momentum, creating a price bubble disconnected from the company's actual financial health. In this case, the social media-driven surge transformed what could have been a rational investment decision into a speculative frenzy, amplifying irrational exuberance and turning what might have been a "wise crowd" into a "dangerous mob."

The sensationalism on these platforms has contributed to mispricing assets, as the stories that capture attention are often not the most accurate or fact-based. For instance, in the case of GameStop, misinformation regarding the company's future prospects and the supposed "war" against institutional investors led many to invest purely based on the narrative, rather than a thoughtful analysis of the company's actual business model. As the price of GameStop soared, the narrative on social media grew louder, reinforcing the perception that the stock would continue to rise despite a lack of fundamental support. This creates a feedback loop, where rising prices and increasing media coverage reinforce each other, further detaching the stock's price from its intrinsic value.

This shift in how information is processed and shared among investors deepens inefficiencies in the market. It challenges the idea that prices reflect the collective wisdom of the crowd and instead suggests that crowd dynamics, influenced by social media and internet forums, can distort market behavior. The rapid spread of biased, emotion-driven views and the herd mentality it fosters can cause asset prices to deviate significantly from their true value, making the market less efficient and more prone to extreme fluctuations. In the modern era, social media plays a critical role in shaping investor sentiment, which, when unchecked, can lead to significant mispricing and market instability.

Modern Realities Driving Increased Anomalies

The diminishing efficiency of markets can be traced to several key factors, with information overload being a prominent contributor. While today’s investors have unprecedented access to data, the sheer volume and frequency of information make it increasingly difficult to distinguish meaningful signals from irrelevant noise. This cognitive overload often leads to flawed evaluations of asset values, as investors struggle to process and interpret data accurately.

Behavioral biases exacerbate this issue. The overwhelming flow of information often results in overconfidence, where investors mistakenly rely on their initial interpretations of data, reinforcing their biases even when presented with contradictory evidence. Confirmation bias further entrenches these misconceptions, making it harder for investors to revise their views and adjust valuations in light of new insights.

Additionally, investors frequently misjudge the predictive power of the information at their disposal, giving undue weight to the strength of evidence rather than its actual relevance or reliability. This misjudgment skews valuations, creating conditions ripe for mispricings. For those equipped with advanced tools and an ability to filter noise from signal, these inefficiencies can represent lucrative opportunities.

Opportunities to Capitalise on Inefficiencies

In the past decade, the explosion of access to retail brokerages and trading platforms has significantly transformed the landscape of equity investing. With seemingly free trading costs and a heightened embrace of equity investing, the democratization of markets has opened doors for individuals and society at large. The rise of gamification has shifted the perception of investing for some segments of the market, turning it from a disciplined financial activity into a form of gambling. Investors driven by speculation and emotional decision-making, rather than analysis, contribute to a market less focused on fundamentals. This kind of behavior can lead to significant market inefficiencies, where asset prices are more frequently influenced by sentiment than by objective data. When a significant portion of the investor base is engaged in such irrational behaviors, it distorts the pricing process, creating an environment rife with pricing anomalies. While these inefficiencies present challenges, they also present lucrative opportunities for active investors who are disciplined, well-equipped, and able to identify and capitalize on these pricing errors.

Leverage Data to Improve Pricing Accuracy

With an explosion of available data, the potential for pricing errors has also increased. Active investors who build advanced systems capable of processing and analyzing vast datasets are better positioned to identify these inefficiencies. For example, investment managers who utilize machine learning models to sift through large volumes of financial, economic, and social media data have a distinct advantage in recognizing trends and anomalies earlier than others. By developing more sophisticated systems that can extract actionable signals from the noise, these investors can generate excess returns and capitalize on inefficiencies before they are priced in by the broader market.

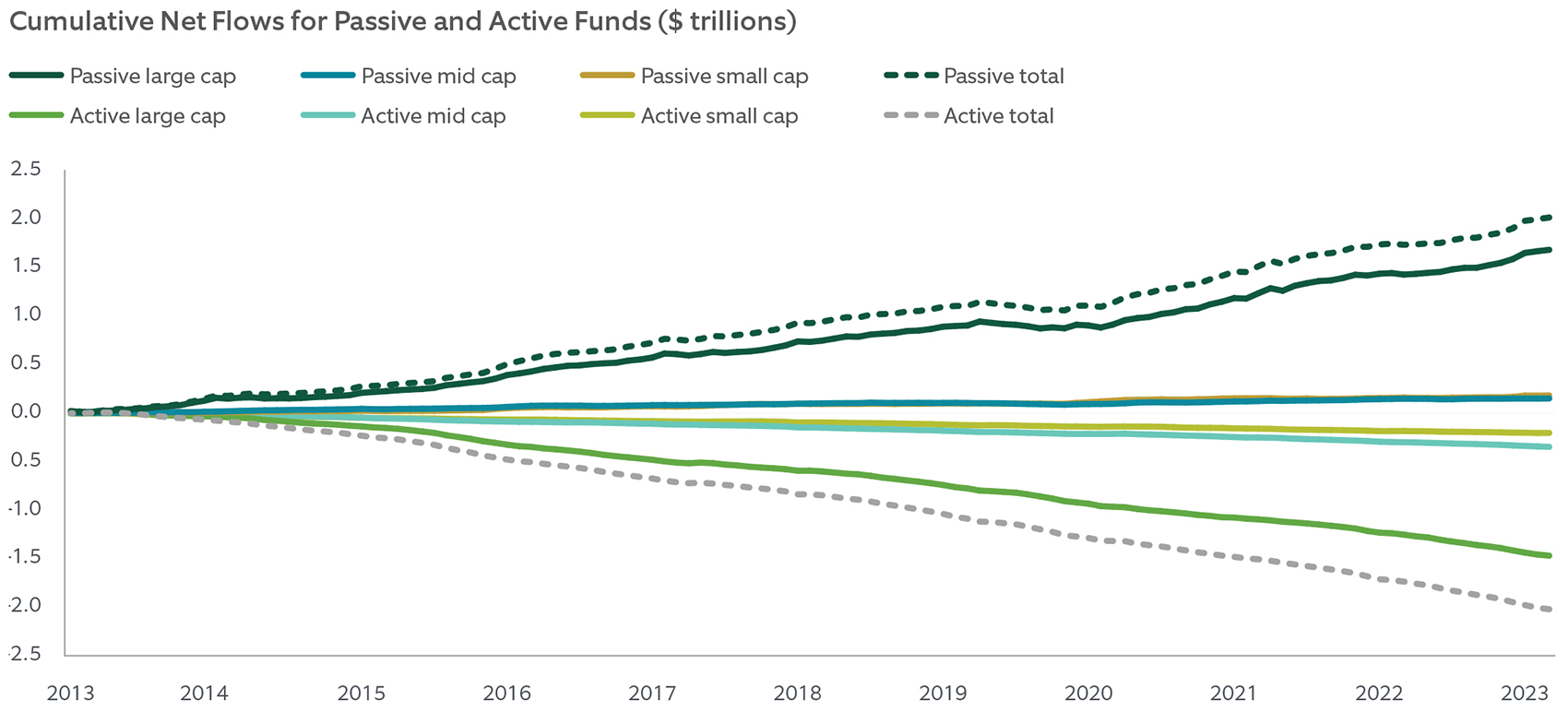

Opportunity in a Smaller Pool of Active Investors

Active investing has seen a decline in recent years, with many institutional and professional investors shifting toward passive strategies. This shrinking pool of active investors leaves more opportunities for those who remain disciplined and focused. As the market becomes more distorted by irrational behaviors and biases, active investors who stay committed to thorough analysis and sound investment principles stand to reap larger rewards. The opportunities for outperformance are greater than they have been in years, provided that these investors can navigate the volatility and effectively identify mispriced assets.

Risk Mispricing Creates Arbitrage Opportunities

In an environment where risk is being systematically mispriced, astute investors can take advantage of this trend to generate returns. Momentum derived factors have consistently delivered strong performance over the past decade, and a portion of this outperformance can likely be attributed to a broader "reach for yield" in the market. Investors who understand the behavior behind these factors can structure their portfolios to capture mispriced risk and benefit from these trends before the market adjusts.

Consequences to Market Practitioners

As market inefficiencies become more evident, a reevaluation of capital market strategies is necessary. For investors, this evolving landscape presents both challenges and opportunities. The traditional view, embodied by the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), asserts that asset prices always reflect all available information, making it impossible to consistently outperform the market. EMH advocates for a passive "buy and hold" strategy, focusing on diversification and minimizing transaction costs.

However, the rise of behavioral finance challenges this view, highlighting that markets are not always efficient and that mispricing offers opportunities for those who can identify it. Investors who can recognize and act on these inefficiencies—whether by spotting early signs or capitalizing on sentiment-driven trends—are more likely to achieve above-average returns.

The implications for corporate finance are equally significant. In an efficient market, equity pricing is always accurate, and firms would not adjust their capital structure based on market fluctuations. But in the context of behavioral finance, companies can exploit periods of overvaluation to issue equity or repurchase shares during undervaluation. By understanding investor biases, firms can optimize their capital structure, lower their weighted average cost of capital (WACC), and enhance returns on new investments. Behavioral finance also plays a critical role in corporate decisions like mergers and acquisitions, where recognizing investor sentiment and biases can determine the success of a deal.